The following post is a transcript of an essay by Matthew Manos originally written in December, 2012 for Ashoka.

Empathy is a really big word in design, specifically in the practice of “Design Thinking.” However, this article examines a different role for empathy in design, one that is very frequently overlooked.

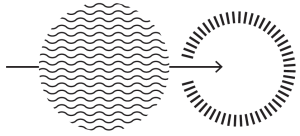

In Design Thinking, empathy is what kicks off a project—it is the first step in understanding what the end user might need by being able to get hands-on experience understanding their problems and “pain points.” The space in which empathy is quite absent from design, however, is in communication materials, a medium that is historically sympathetic. Sympathy, as opposed to empathy, does not foster a deep understanding or emotional connection. Empathy, as opposed to sympathy, is a way for us to develop our understanding by sharing an experience.

If I told you that close to 97 percent of nonprofit organizations, and the designers that power them, are marketing their causes in immoral ways, would you believe me? If you look at the landscape of advertising, communication, and strategy that dominates the social sector, you will notice one thing—they are all driven by sympathy. This is not a new observation, and it isn’t a new phenomenon either. If you go back a few decades, you will still see the same tactics that all stem from the power of sympathy. Miss Sympathy and her best friend Mr. Guilt have been used for years because they are widely accepted as the most successful ways to draw attention, spark outreach, and inspire a potential donor…or so we thought.

While sympathy and guilt seem like strong tactics, the implications of their use are actually counterintuitive to the end goals of nonprofits for at least the following three reasons:

1. Sympathy Dehumanizes

You know those ad campaigns and infomercials on TV that feature a starving African child or an impoverished family in India? Take a look at that footage again. While the intention of these images is to draw attention to an issue of significant importance, the result is often an unintended “dehumanization” of the people these organizations are seeking to support. These images are not of children; they are of a problem. Your heart and mind are not drawn to the spirit of a child or the personality of a family. Instead, your eyes, through the power of advertising, are drawn to the deformity, the skinny stomach, the wound. This one detail removes the human qualities of the people whom the images aim to portray.

2. Sympathy Removes Us Further From the Cause

People don’t always respond well to what they cannot understand. This doesn’t make us bad; it is just how we are. On the morning of 9/11, when the twin towers collapsed, we all stood in shock. But the night before, when many of us watched one of those action movies featuring an exploding skyline, we didn’t even budge. Why? Because we never thought it could happen to us; we understood the images portrayed in that film as something other than our own reality. By dehumanizing the people behind the camera, advertisers are doing the same thing. As a result, our own personal relationship is even further removed from the context, and thus we are not as likely to give.

3. Sympathy Makes Us Feel Bad

Simplest of all, making us feel guilty makes us feel bad too. Pro tip: If you want potential supporters of your cause to fall in love with your brand, don’t make them feel bad about themselves. Has Coca Cola ever told you that you were a horrible person? Of course not! So why should nonprofits adopt that model? I can’t tell you how many times I have walked by a canvasser who has asked me if I care about gay rights, or about the planet, or that children are starving in Africa, oftentimes while I am holding a bag of leftovers. The answer: of course I care. The assumption: by not stopping to sign my name or donate my food, I don’t care. The awkward encounters that result from scenarios such as this, as well as the uncomfortable feelings from watching one of those infamous commercials, makes us feel bad in a very unproductive way.

But don’t worry … it’s not all bad out there. In fact, something big in the past five years has really started to have a positive impact on the marketing strategies of nonprofits. Social media marketing in the social sector has begun a significant transformation in the way people engage with causes. The fundamental value of social media is that it calls for a dialogue as opposed to a monologue. In the Mad Men days of advertising, people would be told what to buy through looking at a poster. In the social media days of advertising, people are able to have a direct dialogue with organizations of interest. The introduction of dialogue has the power to cultivate shared experiences, the driving force of empathy. Three specific organizations that are engaging successfully through social media are the Human Rights Campaign, KaBOOM!, and UNICEF.

The team at verynice is tackling this issue in our current collaboration with Waner Children’s Vascular Anomaly Foundation (WCVAF), a nonprofit providing medical treatment to children who suffer from severe deformity. We recently conceptualized a strategic plan that allowed us to explore what it means to launch a campaign driven entirely by empathy. The current photography leveraged by WCVAF does not portray images of the children – instead, they portray images of deformity. Working with our volunteer photographer, Ethan Yang, my business partner Bora Shin developed a creative direction for the images that leveraged a photo-journalistic style to tell the story of one of WCVAF’s patients. As a result, when you flip through the final images we selected, your eyes completely lose sight of what is “different” about the child because your heart and mind are too distracted by her beautiful spirit. You realize that she is just like any other little girl—she is a daughter, a big sister, and a friend. The campaign will launch next year, so keep your eyes peeled!

Instead of focusing on making people feel guilty for not assisting in the efforts of any given cause, we need to guide people to the realization that their assistance is necessary through empathy. By portraying the victim of a cause in as human a way as possible, we are putting the donor and the victim on the same level. We are enabling others to relate to each other in order to build a strong community of change-makers. When people remember that skinny little boy, not by the dominance of his ribs in a photograph but instead by the spirit of his own humanity, we can then craft a successful campaign driven by humankind’s desire to help one another.