When I was young, I remember a moment in a local grocery store when I saw a coupon for a free toy. I looked to my dad and said, “Look, a free toy!!!” His response to me was: “Matthew… Nothing in this world is free.” I’ve spent the majority of my professional career actually trying to prove that sentiment wrong and, so far, I am not quite sure if I have been able to or not. Over the past decade, I have been investigating the cultural relevance and promise of pro-bono. As a result, put in a less fancy manner, I’ve become obsessed with “free stuff” and more specifically, the role of “free” in business, and the importance of alternative economies in our society.

“Between digital economics and the wholesale embrace of King’s Gillette’s experiment in price shifting, we are entering an era when free will be seen as the norm, not an anomaly.” – Chris Andersen

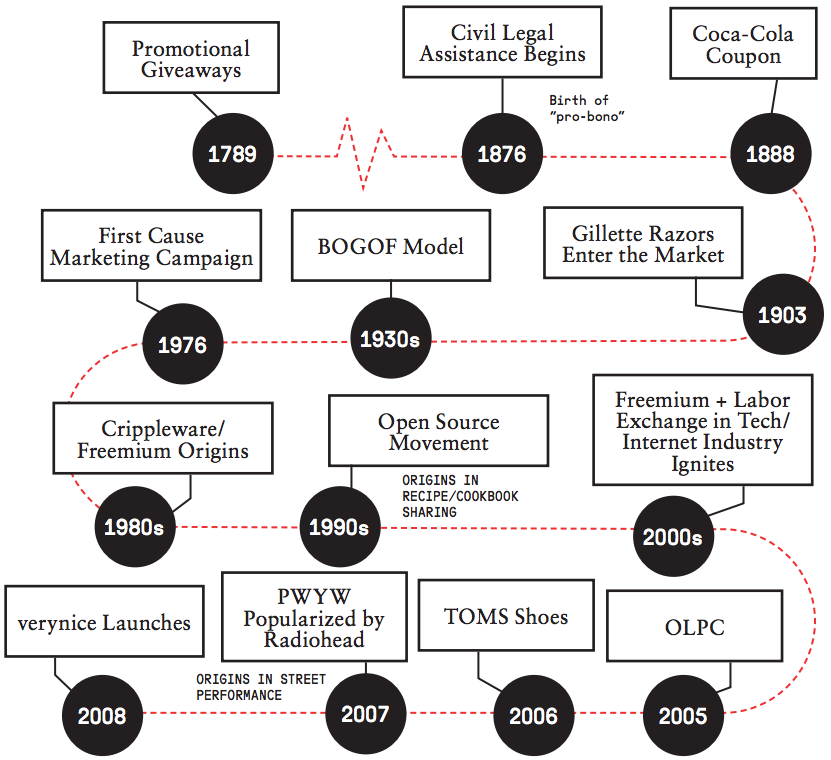

“Free stuff” has been at the core of business strategy for centuries. Sure, the fundamentals of capitalism have always been rooted in the design of models for exchange and value creation, but what often goes without much recognition in the mainstream is that client and consumer acquisition has long begun with a free gesture, such as a free initial consultation, or a free sample. That gesture and the role of “free” in business can be categorized into two typologies: Strategic and Altruistic. While very separated in intentions, these two takes on “free” in business have actually historically yielded much inspiration on one another, and clear lineages can be traced between models. Let’s take a walk through time together to get our heads around the role of “free” in business. Specifically, let’s explore a series of both historical and contemporary models of business in which “free” is at the heart of the strategy in order to understand how “free” in business can actually go beyond opportunity and instead be seen as an expectation for business, something that can transition into the altruistic side of things.

There are two kinds of business: product and service. While product-oriented business deals with physical goods that are manufactured and require distribution, service-oriented business focuses on the value of time, experience, and the sharing of knowledge. Think for a second about a pair of really nice leather shoes in comparison to an hour long conversation with an attorney. While both actually cost a customer the same amount of money (~$200), they both reside in completely different business landscapes, and therefore are perceived very differently in terms of value both by the consumer and the provider. Likewise, if we gaze a few layers beneath the surface of these engagements, we will soon find that the inner-workings of both trajectories are just as different as their perceived value. In fact, both are so different from one another that they actually require completely different modeling strategies to ensure success and scalability. So why is this all so important to leverage as a preface for the words to come? Because “free” can mean a lot of things in business, and the histories of the product side and the service side, as well as their evolution, have quite different stories to tell.

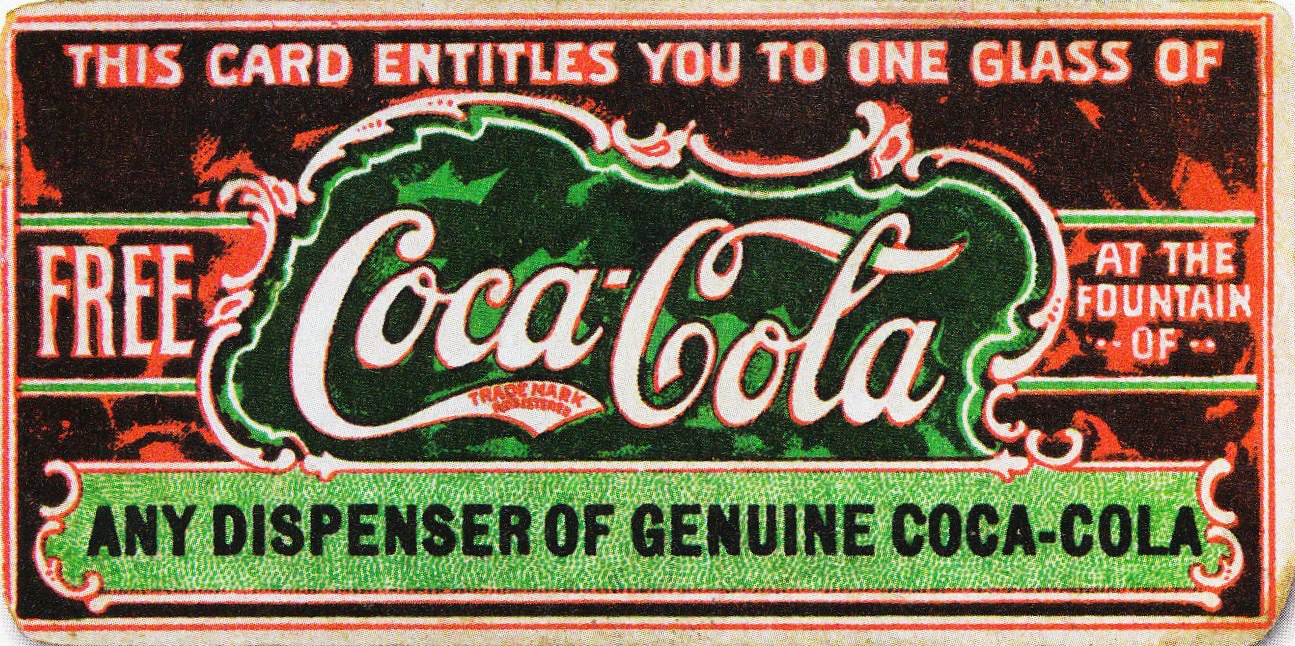

Thanks to Wikipedia, I can tell you that the first known promotional giveaway item was actually a series of commemorative buttons that dated all the way back to the days of George Washington’s election in 1789. To this day, giveaways, more popularly referred to as “swag,” continue to be used in and out of the political space at gatherings such as corporate events and conventions. That said, from my perspective, the real godfather of “free” in product-oriented business is not the promotional giveaway, but instead the promotional coupon. While coupons were made popular primarily during the great depression due to the need for value and free goods, the legacy of the coupon can actually be drawn back to the year 1888. Shortly after incorporating in Atlanta, one of the Coca-Cola Company’s key partners, Asa Candler, played a significant role in transforming the company into the profitable business it is today by experimenting with innovative advertising techniques. One of these techniques was what many consider to be the first-ever coupon. The coupon itself promised a free glass of Coca-Cola from any dispenser that sold the beverage. What was the result of this deal? Well, within less than 10 years, one in nine Americans had enjoyed a free glass, and right at the end of the 19th century, Candler had announced to his shareholders that glasses of Coca-Cola were being served in every state across the US.

Shortly after the launch of the coupon program by Coca-Cola, the method of promotional advertising started hitting the mainstream thanks to some more help in proving the potential of coupons by C.W. Post, the guy that decided putting coupons on the back of a cereal box was a good idea (thanks for the tip, Wikipedia). Turns out he was correct! According to NCH Marketing Services, Inc.’s Annual Coupon Facts Report, more than 2,800 different packaged-goods companies actually offer a coupon for discounts on their products. In 2012 alone, 2.9 billion coupons were redeemed.

So what exactly is the point of coupons? Well, they of course make consumers happy, but the immediate implications are far more strategic then that. Coupons can help convince a consumer to try your stuff. As we saw with Coca-Cola, 8.5 Million people were able to take a sip of their soda as a result of their free trial coupon. While there are no statistics that I can find to prove this, the company would arguably had a far more difficult time building the god-like brand recognition it has today if it were not for that little piece of paper. Beyond brand building and lead acquisition, though, coupons have also been leveraged as a tool for market research and, more specifically, price sensitivity. By sending different types of coupons to different demographics and regional markets, businesses are able to get a sense for what kind of price marks can get them the most bites.

More broadly defined, a coupon can really be understood as a “deal” – a discount, or an opportunity for the consumer to acquire something new at less cost to them. As we will explore, the idea of “discounted consumption” that the coupon blazed a trail for has evolved into several models, some new and some old, but all of which will be defined and analyzed over the next few thousand words: BOGOF, Freemium, PWYW, and pro-bono.

The phrase “BUY ONE GET ONE FREE” (also commonly referred to as BOGO or BOGOF), created by Shara ‘BOGO’ Jacavage, is a marketing strategy that often graces window displays, interior signage, and hang tags at every big-box store across several retail-oriented sectors. In the instance of the BOGOF model, “free” is an integral component of this model of business, but the intentions are purely strategic, and thus the model strays far away from altruism. Instead, it is a strategic means of persuasion that sub-consciously inspires consumers to perceive the value of exchange to be much greater than it really is. What does this mean for stores? Put simply, it is one of the most profitable forms of sales promotion, even more so than 50% discounts.

“[…] assume that you value your first pizza of the night at $15.01 and the second at $5.01 and let’s say it costs the store $2 to make each pizza. If the pizza store has a buy-one-get-one-free offer at $20 then you will buy two pizzas and the store will have profits of $16 ($20-$2-$2). But if the store sells pizzas for half price, $10 each, you will buy just one pizza and the store will have profits of just $8 ($10-$2).” – Marginal Revolution

Now, I know. There are a lot of numbers in that example. Truth be told, I haven’t been required to take a math class since I was 17 years old, BUT if you do some quick math on the above scenario, you will quickly realize that the store in this pizza-night scenario actually made double the profits while simultaneously giving you one pizza for free. According to IGD, a data company that monitors supermarkets, a quarter of all shoppers buy goods because they are part of a buy-one-get-one-free offer. So is this model sneaky or genius?

I once found myself in Jerome, Arizona wandering around one of those tchotchke stores that are filled to the brim with questionable “antiques” and a plethora of corny statues. Behind the counter, I stumbled upon an amazing sign that served as a direct critique of this infamous BOGOF model as it read: “BUY ONE FOR THE PRICE OF TWO AND GET THE SECOND ONE FREE.” While intentionally comical, and not intended to be taken too seriously, the sign actually captures the real genius behind the BOGOF model’s long-standing success in the retail environment. The BOGOF model introduces business owners with the opportunity to increase the perceived worth amongst consumers through strategic mark-up, and it also introduces an opportunity to “kill two birds with one stone” by enabling the acquisition of at least two products per one consumer. This is a textbook example of “free” as a means to create opportunity for business success in the for-profit space, but what would happen if this model was leveraged for the greater good?.

Sponsorship models have long been leveraged in the non-profit space. Some of the more famous examples are organizations that allow you to sponsor a child through a monthly commitment to provide monetary support to make access to clean water, an education, healthcare, and more possible on a daily basis. Another famous example of sponsorship in the non-profit space is Heifer International, an organization that allows you to sponsor villages abroad by purchasing a goat for them. Likewise, Charity Water is a popular donate-to-sponsor organization. But what would happen if donors could sponsor, but also receive something in exchange for their donation? One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) is a non-profit organization that aims to do exactly as its name suggests: provide one laptop for every child.

“We aim to provide each child with a rugged, low-cost, low-power, connected laptop. To this end, we have designed hardware, content and software for collaborative, joyful, and self-empowered learning. With access to this type of tool, children are engaged in their own education, and learn, share, and create together. They become connected to each other, to the world and to a brighter future.” – OLPC Mission Statement

Upon its debut, with its focus resting on children in third world scenarios that have little access to technology, the organization originally set out to create a laptop that would only cost $100.00. While affordable to the average American, the ability to whip out one hundred bucks in certain countries abroad is quite a privilege. In lieu of this, OLPC leveraged the BOGOF model in a way it had never been leveraged before. Put simply, members of privileged nations can elect to purchase a $100 laptop for the price of $200 in order to sponsor the purchase of one device for someone abroad who cannot afford it. In many ways, this model of business can be described in similar terms to that comical sign I had brought up earlier, but with one slight modification: ““BUY ONE FOR THE PRICE OF TWO AND GIVE THE SECOND ONE AWAY FOR FREE.” The buy one give one model, popularized by OLPC, is unique in both its practicality and its scalability. Through transparent pricing models, consumers are able to know exactly where their purchase dollars are going, and are therefore compelled to give. Arguably, not many first-world inhabitants actually want the OLPC machine due to its irrelevance in our privileged society. Instead, these purchases are being made with the desire to give back. This fact shines light on the fact that giving can compel consumption among many. Therefore, the model goes beyond being a unique fundraising method, and is actually a strong model for business and revenue generation at a larger scale.

Borrowing from the OLPC model, Blake Mycoskie, the founder and current CEO of TOMS shoes has made a name for his “One for One” model through the introduction of this line of thinking to the for-profit sector. For every pair of shoes that a customer purchases, a pair is donated to a child in need. Upon its introduction to the market place, this model spread like wild fire amongst small businesses on a global scale and, as a result, there are now many instances of replication across the product-oriented business landscape that borrow the same tactic. “It’s like TOMS, but for ___” is a phrase that can be commonly overheard at social enterprise startup events. Part of the reason the model is so successful is due to its ability to make giving back an accessible act. The consumer does not need to go out of his or her way to contribute to a cause, in this scenario; instead, they need only purchase products that they already need in their daily lives. The company takes it from there. Like the OLPC model, “One for One” relies on the relevance and desire for the product both by the purchaser and the beneficiary. Because of this reality, the “one for one” model, as a for-profit business strategy, does gather a lot of skepticism and critique in regards to the authenticity of the model’s intentions due to the fact that the model can only succeed in the market place if the problem continues to exist. Intentions aside, TOMS Shoes, and other companies leveraging the One for One approach have been able to create significant impact in terms of the volume of their contributions. As of October 2011, TOMS has been able to give away over 2,000,000 pairs of shoes to children in need.

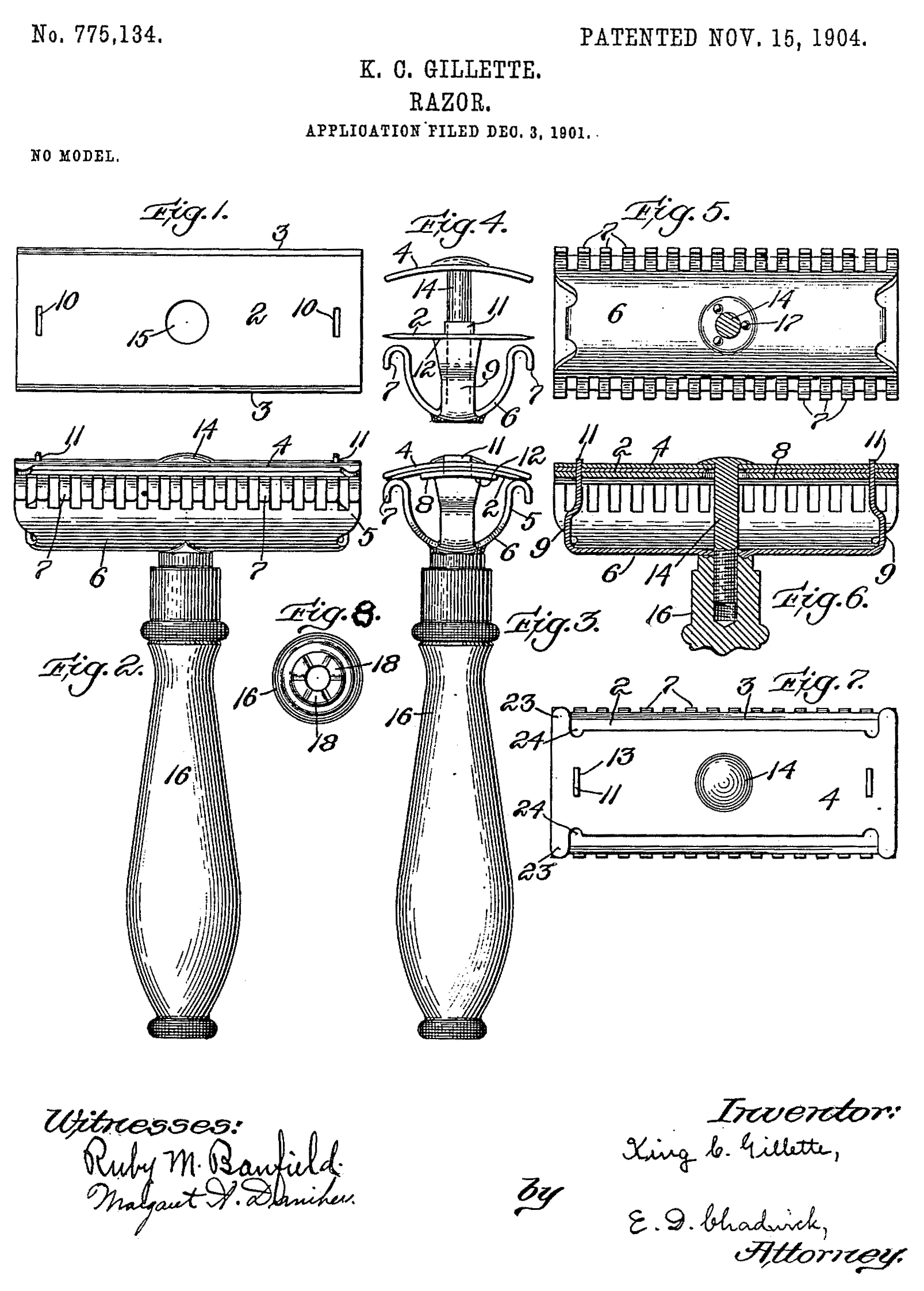

A genre of business that describes the opportunity of BOGOF well is known as cross-subsidies. The idea is that something helps pay for something else. For example, drinks are sold at a premium to reduce food costs in restaurants. Video game consoles are sold at a price point that is less-than-break-even for the manufacturers, but the games themselves are sold at an enormous markup. The majority of economic models leveraged by business, in fact, rely on this. While “BUY ONE GET ONE FREE” has proven to be a successful spawn of the overarching cross-subsidy strategy, let’s dip into another interesting business model that equally stemmed from the same genealogy of the holy free coupon… the Gillette Model. Better referred to today as “freemium,” the Gillette model was made popular by King Camp Gillette, a brilliantly conflicted figure amongst the greatest entrepreneurs in the 19th and 20th centuries. Gillette is best known for the invention of his disposable razor. The concept, unveiled just 5 years after the Coca Cola coupon hit the market, pioneered a brilliant new model of business known as “The Razor and Blades Business Model” and, more commonly today, as “Freebie Marketing.” While working as a salesman for the Crown Cork and Seal Company, Gillette saw great opportunity in the design of a product that served its purpose, and then was tossed in the trash. These one-time-use products foster long-term, repeat, customers. While shaving his face one morning with a razor that lacked a strong edge, the idea to create a thin sheet of razor blade came upon Gillette, thus giving birth to the Gillette razor we have today. Perhaps a lesser known side of Gillette is the fact that, aside from being a successful business man, he was also a utopian socialist. This passion inspired Gillette to be a prolific writer of books that sit between the genres of fiction and non-fiction. Gillette was an obsessive planner, writing hundreds of pages that aimed to highlight every last logistic element and business plan for his utopian vision. In his first novel, “The Human Drift,” Gillette wrote about the chaos of contemporary existence, and a prospectus for the alternative world he dreamed of building to fix it (which just so happened to be based behind the Niagara Falls).

King Camp Gillette was best known as the founder of Gillette Razor company, but what really made the company a phenomenon was not the sharpness of its blades, but the model of customer acquisition. With razors being sold for extremely cheap / practically free, the company’s revenue is actually focused on continuous purchases by its customers, namely: razor re-fills. Truth be told, while the razor itself is very cheap, the blades are very NOT cheap. This model is an example of the use of “free” in business in order to acquire long term customers instead of one-off buyers. Around the time that the Gillette razor was launched / brought to market, the primary concern of the market was to actually create products that would last a lifetime. For better or worse, Gillette’s model brought the attractiveness of “perishable products” to the forefront. In more modern times, this model has seen wide-adoption, but especially amongst technology businesses. Let’s think about the Sony PlayStation for a second. The console itself, priced at roughly $300, is quite affordable. So affordable, in fact, that every time a video game console is sold, the respective company (Microsoft, Nintendo, Sony, etc.) actually loses money.

An even more modern evolution of Gillette’s “Razor and Blades Business Model” can be found in the majority of contemporary SAAS (Software-as-a-service) businesses, mobile games, and the majority of the “web 2.0” giants we all know and love. About 80 years after the launch of the Razor and Blades model, in the 1980s, a popular method of digital product marketing and distribution known as “crippleware” emerged. The crippleware namesake comes from the built-in limitations the floppy disks have. Like the Gillette Razor, the content stored on the floppy disks is not built-to-last, and therefore easily inspires upgrade. Under the crippleware model, via floppy disks, users can engage with software in order to test it, but will have a limited user experience, in exchange for not having to pay anything. If the user wanted to explore more, they would be forced to purchase the complete set. Likewise, many major tech companies operate this way. LinkedIn, for example has both a free and a premium account. Flickr, too. The list goes on. Beyond web 2.0 / social networking / SAAS space, the freemium model has also taken the world by storm in the mobile gaming and app space in the form of “in-app purchases” thanks to the persistent relevance of mobile devices in society today. After the iPhone was released in 2006, a whole new market place for entrepreneurs to dabble in emerged: the app store. With many of the first apps being unveiled for free to download, investors and users alike were baffled by the feasibility of giving so much away for free… until an important strategic advancement occurred: the in-app purchase. An in-app purchase typically exists within a free app in which a user is able to purchase more features / functionality at a premium in order to enhance the overall experience. A very popular method of delivery for an in-app purchase, per my own observations, has been in recipe-apps. For free, a user can get a handful of recipes… for an additional $2.99, they can get 100 more. Stepping into the shoes of a consumer, and perhaps reflecting on our own previous purchases for a second, it seems like a no-brainer, right? Yup, that is exactly why the model has worked out so well. To make comparisons across the business landscape, we can quickly see that this try-it-before-you-buy-it type of customer experience can also be found in the service-oriented business space. While the origins are a bit untraceable, for what I’ll go ahead and claim to be “hundreds of years,” consultants have leveraged a very similar strategy for customer acquisition… the “free initial consultation.” Initial consultations in the service-space are very similar, strategically, to the freemium model in the product-space due to their ability to inspire a customer to engage with a service in a way that removes many barriers (cost, commitment, etc.) in order to, hopefully, get them hooked on the value of the service that is being offered. Like the BOGOF and Gillette Models, the free initial consultation can also be related to the umbrella term of cross-subsidies due to the payoff that can come from a continued relationship with the client, on a paid basis. Often considered a win-win scenario, consumers can also leverage the model to their advantage through the ability to essentially “test the waters” on a product or service before making an investment that can be a bit hefty in some scenarios.

As we saw earlier, cross-subsidies like the Buy One Get One Free model have been able to evolve over time to incorporate intentions that go beyond opportunity, so what about this freemium model? How has that model evolved to the space of civic engagement and social obligation? Since the beginning of mankind, information has been given away freely… middle-school US History class tells us that the pre-Columbus era was filled with Native American campfire stories… for generations, recipes have been passed down amongst neighbors and family members… What about in business? Is there such thing as an institutionalization of free knowledge exchange in our society? Yes. In the 1990s this common act of “sharing” knowledge became a thing: the open source movement. Like the freemium model, open-source software begins with something free and openly available for all to use. Unlike the freemium model, however, there are no “tiers” for engagement, meaning the information is always free, and a premium does not actually exist. The open-source movement has continued to gain traction in recent years, most notably in the maker culture with software and hardware projects like Processing and Arduino, languages and platforms, respectively which hope to inspire the use of programming as a tool for the visual arts. Thousands upon thousands of users that leverage things like Processing and Arduino make their source codes available for all to learn from. It is a community of makers that want to learn from each other in order to make something much bigger then themselves. In the service-oriented space, we talked about initial consultations that are provided at no cost to the client with the intention to sell them on ongoing or future consultations that are “sold” at a premium. When you take away that intention to sell the interested party on future engagements at a cost, you get pro-bono.

“Without equal access to the law, the system not only robs the poor of their only protection, but it places in the hands of their oppressors the most powerful and ruthless weapon ever created.” – Reginald Heber Smith

Pro-bono (which is short for pro bono publico: “for the good of the public”), has roots that are set deeply within the legal industry, traceable to years as early as 1876, an origin date that precedes the invention of the coupon in 1888 by over a decade. “Civil legal aid,” as it is referred to, began when the German Society of New York launched an organization that had the specific goal of protecting recent German immigrants from exploitation in the states. The dedication to leverage legal aid as a means to protect those who could not access protection was soon extended well outside of the German immigrant population and eventually the Legal Aid Society of New York was founded in 1890.

Legal activist, Reginald Heber Smith, in 1919, wrote a text titled “Justice and the Poor” that was crucial in the advancement of thought leadership around the necessity of pro-bono, eventually inspiring the American Bar Association to create the minimum pro-bono obligations that law firms today are required to uphold in their respective practices. Pro-bono soon became prevalent in fields outside of the legal industry, but the first trace of that can be found in 1942, when the Ad Council, a non-profit organization dedicated to the development of public service advertisements (PSAs), was formed. To deliver these critical and iconic messages (think Smokey Bear) to the American public, many key advertising agencies and design firms were leveraged on a pro-bono basis.

To this day, pro-bono has continued to be leveraged by non-profit organizations and government agencies in order to gather the same kind of response that more privileged clients can have as a result of their marketing and design budgets. Thanks to activists like Aaron Hurst, the founder of the Taproot Foundation, as well as government programs like the Committee Encouraging Corporate Philanthropy (CECP), and the Billion+ Change campaign, pro-bono is now valued as a resource that extends across a diverse range of fields and industries from Human Resources to Business Management to Graphic Design, and more. Great strides have been made, especially in the past 5 years, by campaigns that call for at least a 1% ongoing commitment to pro-bono, or an annual weekend-long hackathon of sorts to promote the aid of non-profit organizations. Thanks to these initiatives, pro-bono is now a term that is in the vocabulary of many businesses, big and small.

While many of the examples we have gone through thus far show a clear benefit relationship and hierarchy between customer and business, there are also examples of “free” in business in which the individual seemingly has the leg up on the business. Key word here is “seemingly.” These kinds of engagements actually are known as a value exchange. Similar to ancient methods of bartering, value exchange calls for a trade, of sorts, though the immediate trade, on the side of the consumer, actually seems non-existent. Two strong examples of value exchange in contemporary business include platforms that require you to contribute a bit about yourself as well as digital products that are heavily populated with ads. The two, in fact, go hand in hand. Think about Facebook. You don’t pay anything to use it, right? You never will, in fact. Well, that’s just what it feels like. In reality, Facebook (and really any free social networking platform) is profiting big time off of you, and you indeed are paying them, just in ways that aren’t so obvious on the surface level. By acquiring data about yourself, people like Facebook are able to leverage your information in the interest of ad providers that are willing to pay the big bucks just to get an ad in front of someone that is just like you. Google is the same way. Many people don’t realize this, but Google’s primary value exchange between customer and business is your willingness to search using their platform. Like Facebook, Google is “seemingly free,” but in reality, you are paying through your comprehensive search preferences.

The final example of “free” in business that I would like to take a look at is the Pay What You Want model (commonly referred to as PWYW). While PWYW can be traced far back in time to the days of street performers, the model entered the mainstream’s consciousness in 2007 through a successful use of the model by Radiohead, in conjunction with the release of their new album, In Rainbows. Quite timely, the album itself was released at a time when conversations around the value of digital music were at an all-time high. People were pirating left and right in the early ‘00s, and not many musicians knew what to do about it. Radiohead decided to take it upon themselves to leverage this reality in music as an opportunity by allowing fans to make their own decisions regarding the value of their music. As a result, listeners could choose to pay nothing and receive a brand new album at no cost, or, perhaps, pay a few hundred bucks out of gratitude for the chance to determine value on our own. The results were groundbreaking as it was quickly found that the listeners, after averaging all transactions, were actually paying slightly more for the album then the traditional price point. The model is now being used more frequently, specifically amongst musicians, but also by authors, and continued success has been found as a result of putting a little faith on the fans.

As we’ve been able to see, business models, at large, carry heavy lineages. Though Gillette could never have even imagined a world in which people would make in-app purchases, his model has lived on in such a drastically different technological landscape. Likewise, marketers during the great depression likely could never fathom the idea that society would someday prefer to “give one” instead of “get one.” Funny how that works, isn’t it?

–

1. Coca-Cola 120th Anniversary The Coca-Cola Company Time Line – 120 Years of Innovation2. NCH Annual Coupon Facts Report, 2012.

3. McKenzie, Richard B. Why Popcorn Costs So Much at the Movies: And Other Pricing Puzzles. ISBN 978-0-387-76999-8, 2008.

4. Buy one get one free, from Marginal Revolution. Retrieved 2008-01-05

5. Wallop, Harry (2008-07-07). “Food waste: Why supermarkets will never say bogof to buy one get one free”. Telegraph. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

6. TOMS Giving Report, 2013.

7. “History of Civil Legal Aid” – National Legal Aid and Defender Association, http://www.nlada.org/About/About_HistoryCivil

8. Taproot Foundation – History of Pro-Bono: http://www.taprootfoundation.org/about-probono/pro-bono-history